The post-Halloween-pre-Christmas curmudgeon that is November sure can feel like a slog; a dark, cold, wet slog. As the weather gets worse, the last thing you may want to do is get up and get out of the house to do some bird watching, especially down by the coast where the wind can really bite you. So I figured we’d bring the coastal birds to you with this post. Get yourself comfy and have a gander at our goosiest duck. This month’s bird is the Common Shelduck (Tadorna tadorna), known as Seil-lacha in Irish.

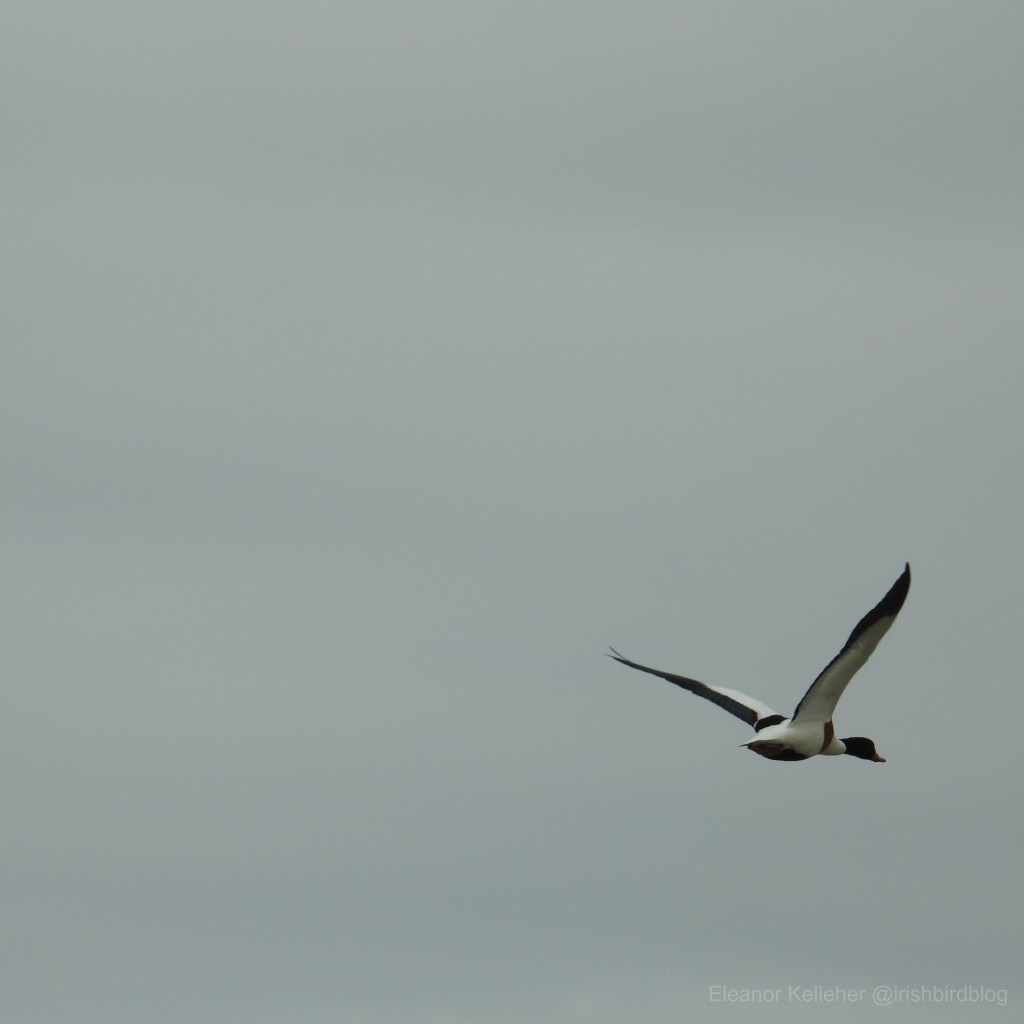

Shelducks really are some of our most striking waterfowl. They remind me of the kinds of ducks you’d see in an old landscape painting in a gilded frame, hung in someone’s library. Having almost-black heads with a subtle green sheen, their cherry-coloured bills stand out starkly against their predominantly white bodies. They’ve got a belt of chestnut coloured feathers across their breast and black scapulars (shoulder blades, for the uninitiated) that sort of evoke the image of an outfit that someone who shops exclusively at M&S might put together.

But I think the thing that really sets them apart from the rabble of our common ducks is their posture. They stand quite upright, and really do resemble geese rather than ducks. In fact, if you take a look at this next picture, you can see they’re about the same size as the actual geese standing not too far away!

Looking at their colourful plumage palette, you might think they were migrant visitors, and we do happen to get an influx of these birds in winter from Scandinavia and the Baltic. But shelduck live here all year round! Strangford Lough in Co. Down is an important site for them, with over 3,000 birds recorded there in winter. Closer to us, there’s a population of 1,000-to-2,000 in Dublin Bay, a respectable number if I may say so myself.

They mostly subsist off of shellfish and invertebrates, but we actually happen to know this duck’s favourite food! It’s Peringia ulvae, a name that sure does roll off the tongue. They’re more commonly known as Laver spire shells, or just plain old mudsnails, and they can be found in almost all the estuaries of Ireland. They’re a vital food source for shelducks and other overwintering waterfowl and waders. So the next time you pick up an empty spirally shell on the beach, it would be a safe guess to say it’s previous inhabitant was eaten by a bird.

Being ducks, they can be found pretty much all around the Irish coast. But as is seen with other coastal birds lately, they’ve steadily been moving inland, where they’ve been known to take advantage of farmland, lakes, reservoirs, and, surprisingly enough, pig fields (maybe the muddy fields remind them of mudflats?).

The first time I ever saw them, I was on the DART heading to Dún Laoghaire. I was watching out for the Booterstown station, because that was when it was time to text the person I was going to meet to leave their house, and spotted dozens and dozens of shelduck in the Booterstown Marsh. At the time, I wasn’t very well-versed in birds and had no idea what these strange, exotic ducks could be. I immediately texted Eleanor a very blurry picture that showcased the grubby DART windowpane rather than the ducks, and learned all about them from her. I can still picture them arranged on the little island and bobbing about in the marshy reserve. Anytime I’m on the DART I look out at Booterstown in the hopes of seeing them there again now that I know more about them, but alas, so far I have not spotted them there again.

Shelduck are ground-nesting birds. An interesting quirk of theirs is that they will take advantage of existing holes in things like trees to nest and lay their eggs in. They’ve been known to take over disused rabbit burrows to use as nesting sites, which is a clever way of avoiding predators. Their chicks are precocial, so they come right out of the egg knowing how to swim and find food without relying on their parents. The species has a cute double-act where the chicks will dive underwater to avoid predators and the parents will fly up away from them to act as decoys. When the chicks grow up, they can live for 20 years! (But usually average at around 10).

As seems to be the trend with all coastal birds, the number of shelduck are steadily declining, and they’re currently listed as having amber conservation status by BirdWatch Ireland. To give you a sense of scale for the loss, there were 3,765 birds recorded in Cork Harbour in December 1981 but a peak count of only 694 in the winter of 2019/20. Their numbers in Ireland overall fell by 19.5% between 2006 and 2011, and one can only assume it’s the usual suspects of overfishing, habitat loss, and climate change that are causing this. So while we may have been kind enough to bring the shelduck to you today through the screen, you may want to go out and catch a glimpse of them yourself before they become so rare, that you’ll only ever be able to see them on screen.