Following on from last month’s post, we wanted to talk about a bird who terrorizes coots and all the other birds who live around rivers, ponds, and wetlands. They may take the appearance of a motionless sentinel on the water’s edge, but this bird is in no-way a protector. This month’s bird is the grey heron (Ardea cinerea), known as Corr réisc in Irish.

Have you ever heard that Aesop’s fable about the heron and the fox? The fox invites a heron over for dinner, but serves the food in shallow plates that the heron can’t get at with its thin beak. So the heron then invites the fox over and serves its meal in bottles with long, narrow necks that the fox is unable to reach. The moral of that story was ‘One bad turn deserves another’, and honestly I think it sums up the nature of herons quite well.

Herons are relatively clever, despite what you may think when looking into their large glazed-over eyes. They’re opportunistic, cunning, and most of all patient; something that is keenly showcased by their eating habits. They are excellent hunters who comb the rivers for fish and amphibians. BirdWatch Ireland describes them pretty aptly when they say: ‘Single birds are often flushed when posed motionlessly at the edge of water bodies, coiled, ready to strike out at unsuspecting prey with its formidable spear-like bill.’

But the bounties of the river aren’t enough for these birds, they are also partial to eating small mammals and even baby chicks! For that reason they are constantly being chased away by coots, moorhens, and any other waterfowl looking to protect its young.

Personally, I’ve got mixed feelings on the grey heron. When I was younger it was always a marvel to see them. I wasn’t as well-versed in bird classification as I am now, so I always called them cranes – which I was apparently not alone in, because lots of people on this island mistake them for storks and cranes, or just use the names interchangeably. Storks are actually extremely rare in Ireland, there’s only been five sightings of them since records began, and cranes have been extinct breeding-wise since around the 1700s (although in 2021 a successful breeding pair was found again! So maybe they’ll be the focus of a future post here someday?).

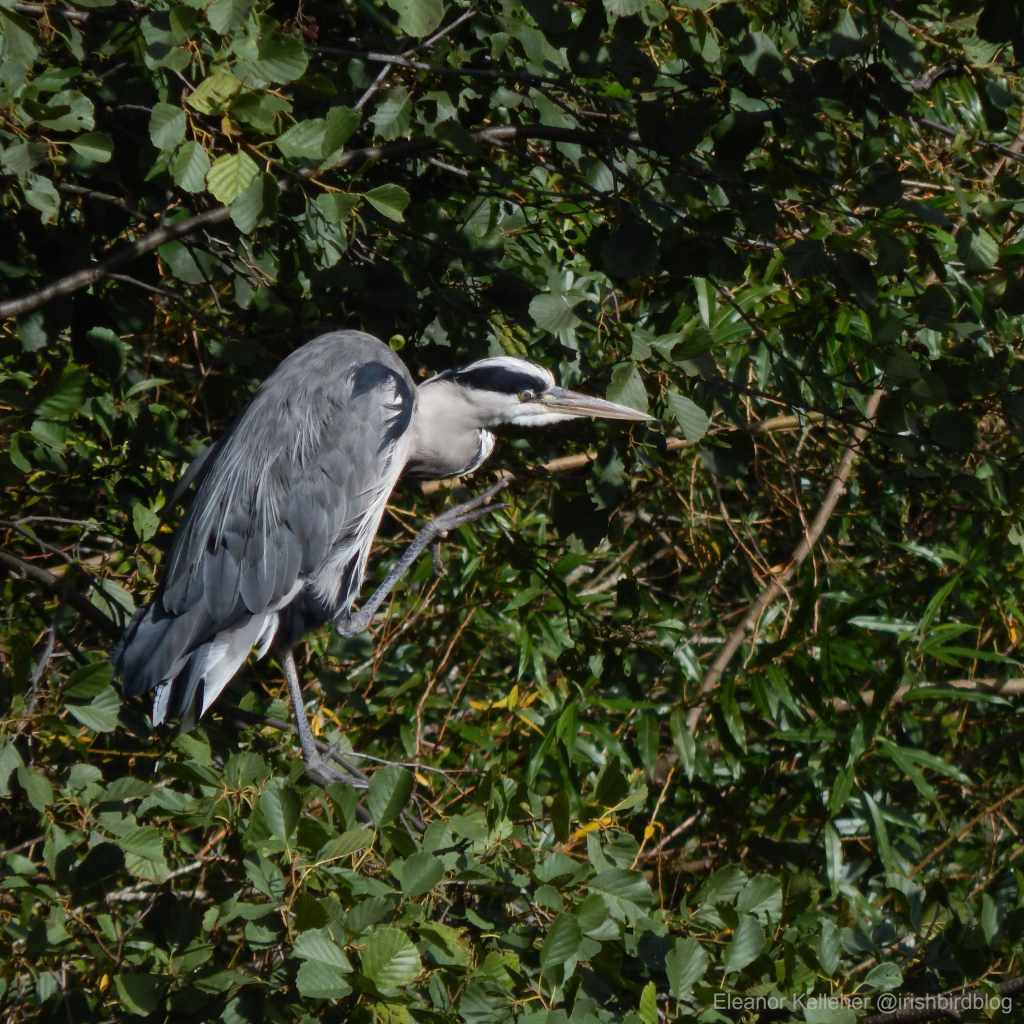

As time has gone on and I’ve had more experiences with these wily creatures, something about the way they bunch up their shoulders and reign in their necks makes me feel like they’re plotting something. You’ll most likely see them wading through shallow water, but they do nest in trees and their gangly bodies often look very out-of-place, even uncomfortable surrounded by leaves and twigs. Coupled with the fact that they’re almost always being chased away by other birds, it’s no wonder they give off nefarious vibes.

History seems to hold the same mixed opinion of the heron as I do. The Ancient Egyptian deity Bennu was depicted as a heron, and the Ancient Romans used herons in their divination practices, so clearly they held positions of importance. Fishermen believed that the heron’s feet must have some way of attracting fish to them, after watching the bird stand seemingly motionless for hours until its prey came within range of its sharp bill, and so carried heron’s feet for luck. But they were also believed to be ill omens that signalled poor weather. Despite this, they also had their uses, such as coating fishing lines in a potent mix of their fat and boiled claws, or using oil made from them for medicinal purposes.

Whether you love them or loathe them, you’ll surely find them standing still as statues on the banks of a river or pond, waiting for their next meal. Now is the right time to go out and see them battling against the coots and moorhens of our waterways, bundle up and head out if you’d like to see the show!

Very informative.

LikeLike